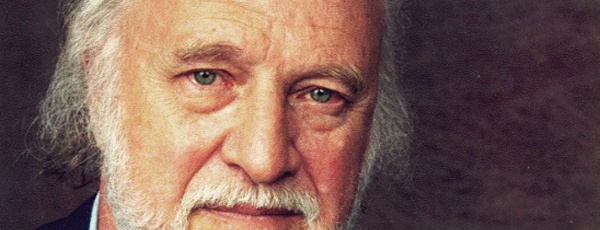

The world—and the future—lost a visionary artist yesterday. Richard Matheson, probably best known as the author of I Am Legend, adapted by Hollywood three times: as The Last Man on Earth, The Omega Man, and I Am Legend. Numerous other of his SF titles have also been made into major movies: Bid Time Return (adapted as Somewhere in Time), The Shrinking Man (adapted twice: The Incredible Shrinking Man and The Incredible Shrinking Woman), What Dreams May Come, Hell House, A Stir of Echoes, and Duel, the TV movie that put Steven Spielberg on the map. He also wrote 14 episodes of The Twilight Zone, and created the TV Series Night Stalker, without which there would be no X-Files, not to mention that show”s countless counterfeits. Matheson, who was 87, was a master of dystopian paranoia, but always managed to imbue his stories with a streak of hope and heroism. In honor of his passing, I”m updating an article I wrote a while back about postapocalyptic movies, a genre which owes more than a little bit to Mr. Matheson.

Say NO to Death: why do we love postapocalypse movies?

ost of us know we’re going to die someday. But we don’t really know this until we approach middle age, when we suddenly find ourselves at the halfway mark between our birth and our death. From this point forward, the time we have left on earth is measurable within our own experience. For the first time, our own death fits inside our head.

ost of us know we’re going to die someday. But we don’t really know this until we approach middle age, when we suddenly find ourselves at the halfway mark between our birth and our death. From this point forward, the time we have left on earth is measurable within our own experience. For the first time, our own death fits inside our head.

Before this universal epiphany, our imagination helps us keep that truth at bay. We imagine, almost unconsciously, that we will never die: that our death will always be beneath the approaching horizon, as it is when we’re young. Even after we come to this realization, we continue to rely on our imagination to keep the idea of our death in a box, made of equal parts panic and denial.

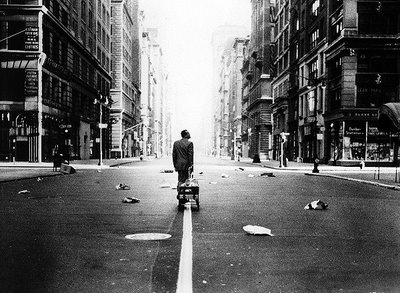

One of the ways this denial fantasy manifests is in postapocalyptic fiction, the ultimate expression of the Kübler-Ross denial stage: “OK, fine, everyone dies”—picture the ultimate SF image of that idea: a depopulated earth—“but not me!”—now picture a man alone in that landscape. Presto! casino online You have the general outline of most postapocalyptic fiction. Of course, the demands of drama often dictate the insertion of other characters (see the Old Testament story of Adam and Eve for an early example of this cliché), so the “I’m not alone after all!” scene is a standard second-act opener in many postapocalyptic stories.

One of the ways this denial fantasy manifests is in postapocalyptic fiction, the ultimate expression of the Kübler-Ross denial stage: “OK, fine, everyone dies”—picture the ultimate SF image of that idea: a depopulated earth—“but not me!”—now picture a man alone in that landscape. Presto! casino online You have the general outline of most postapocalyptic fiction. Of course, the demands of drama often dictate the insertion of other characters (see the Old Testament story of Adam and Eve for an early example of this cliché), so the “I’m not alone after all!” scene is a standard second-act opener in many postapocalyptic stories.

Cliché or not, the genre remains robust. We’re in the middle of what appears to be a surge in the popularity of postapocalyptic storylines: see FX’s series The Walking Dead, and movies such as The Road, The Book of Eli, I Am Legend, 100 Mornings, and of course World War Z, reviewed last week here at drunksunshine.com

One of my favorites of recent years is 100 Mornings. Writer-director Conor Horgan has achieved, with 100 Mornings, the astonishing feat of crafting an almost completely original take on a tried (and tired) genre. There are no piles of rotting corpses in 100 Mornings, no smoking rubble, and no zombies—whether slow or fast. Instead, Horgan’s film is set in the lush green Irish countryside, where two couples are sharing a rustic cottage. Only as the story progresses do we discover that, as the result of a disaster whose nature we never learn—fallout? virus? Rapture?—these four represent a good chunk of the remaining local population. Everyone else, with the exception of some guys with guns who want their stuff and a neighbor who’s reassessing his ideas about neighborliness, is gone. The film remains committed to the originality of its initial setup throughout, as Horgan keeps the drama focused on the characters. A refreshing approach, and an admirable avoidance of the clichés that usually come standard on post-apocalypse movies.

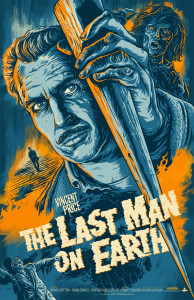

Another favorite, a classic, is the first adaptation of Richard Matheson”s I Am Legend. The Last Man on Earth (available to stream, embedded below) stars Vincent Price in the role later played by Charlton Heston, and then by Will Smith, in later adaptations. As one of the first films in the postapocalypse canon, The Last Man on Earth also gets a pass on any clichés, since it invented many of them. Unlike 100 Mornings, The Last Man on Earth is something of a zombie movie, probably the very first of that subgenre. These shambling bloodsuckers are only half-zombified. They lurch around and bump into things, but they remain conscious; they entreat the protagonist by name—“Morgan! Morgan!”—to come outside and be eaten. But Morgan remains barricaded through the long lonely nights, and only ventures out after the sun rises, when the undead hide from the lethal rays of the sun. Until, inevitably, he stays out too late one evening, civic-mindedly disposing of corpses and methodically inventorying the pantries and shelves of abandoned homes and stores. And of course dispatching any zombie-vampire heencounters. As dated and almost quaint as it can seem after nearly 50 years of escalating zombie gore, The Last Man on Earth shares with 100 Mornings a respect for story and character over effects and cheap scares, and remains despite its age an exceptional example of the genre.

Another favorite, a classic, is the first adaptation of Richard Matheson”s I Am Legend. The Last Man on Earth (available to stream, embedded below) stars Vincent Price in the role later played by Charlton Heston, and then by Will Smith, in later adaptations. As one of the first films in the postapocalypse canon, The Last Man on Earth also gets a pass on any clichés, since it invented many of them. Unlike 100 Mornings, The Last Man on Earth is something of a zombie movie, probably the very first of that subgenre. These shambling bloodsuckers are only half-zombified. They lurch around and bump into things, but they remain conscious; they entreat the protagonist by name—“Morgan! Morgan!”—to come outside and be eaten. But Morgan remains barricaded through the long lonely nights, and only ventures out after the sun rises, when the undead hide from the lethal rays of the sun. Until, inevitably, he stays out too late one evening, civic-mindedly disposing of corpses and methodically inventorying the pantries and shelves of abandoned homes and stores. And of course dispatching any zombie-vampire heencounters. As dated and almost quaint as it can seem after nearly 50 years of escalating zombie gore, The Last Man on Earth shares with 100 Mornings a respect for story and character over effects and cheap scares, and remains despite its age an exceptional example of the genre.