.

.

he new Daniel Radcliffe movie, The Woman in Black, marks another chapter in the continuing revivification of one of the most iconic imprints in the history of movies — certainly in the history of horror.

The British production company Hammer Films was founded in 1934. For the next 23 years, in and out of bankruptcy, Hammer achieved modest and sporadic success with a catalog of around 60 mostly unremarkable films. Then in 1957, Hammer Films changed the face of horror cinema forever, and would henceforth be known to movie fans not as Hammer Films, but as Hammer Horror.

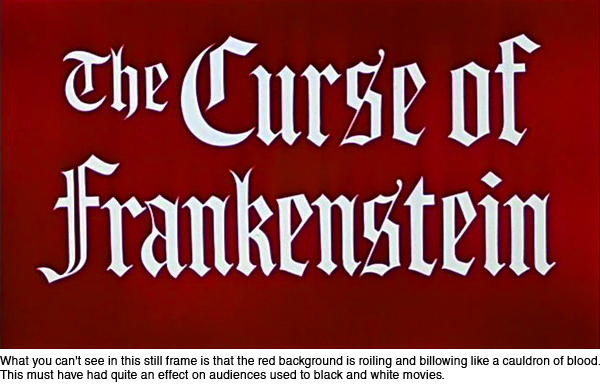

Hammer Films’ transformation into Hammer Horror was marked by a splash of blood red across the screen. With the opening titles of its first color film, The Curse of Frankenstein, it became impossible to talk about Hammer Horror without talking about color.

![]()

![]()

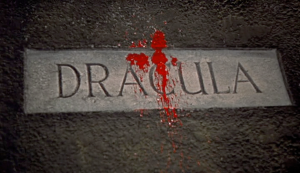

By the time of their next big success, Horror of Dracula, the Hammer Horror aesthetic had become firmly established: the blooms of crimson that punctuated stories set among the oppressive gray stone walls of England’s ancient castles served as the perfect visual representation of the repressed, corseted Victorian sexuality at the heart of this genre of British horror.[1]1 This metaphor would never be more clearly or succinctly incarnated than in the opening shot of Horror of Dracula.[2]2

That this is clearly not blood, but something more akin to red paint, doesn’t matter at all. It’s perfectly in keeping with what makes these movies so universal: the scrim of artificiality, of pure showy staginess, that was the signature visual style of Hammer Horror. Though the screen time devoted to “blood” was much greater in Hammer films than had previously been the norm, earning them the publicity-friendly disgust of serious critics, the ever-present quotes around the “violence” and “gore” in a Hammer film rendered them safe.

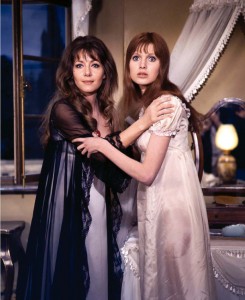

The defiant rejection of naturalism remains one of Hammer’s most beguiling hallmarks. The busty Bardot-esque babes with their troweled eyeliner and bouffant do’s; the white-bright studio lighting over every scene, with the darkest corner of a dungeon just as brightly lit as an “external” scene shot on a sun-drenched forest clearing set on a soundstage—this was play acting: dress-up. So what if a man standing in a windowless cellar holding a candle throws six crisp shadows? It would somehow look wrong if the candle didn’t project a perfect circle of light on the wall. A Hammer film is like a Halloween pageant. Like a marzipan jack o’lantern.

The Hammer Horror style proved to be extremely influential, and was a rare example of American filmmakers importing an influence rather than exporting it. Ultimately, this wide-reaching impact became Hammer’s undoing, as the studio struggled to compete with the imitators it had spawned. Hammer sputtered like a candle in a drafty castle through the 70s, trying anything and everything to stay afloat: reducing budgets, increasing bust sizes, adding gore, removing clothing. After an ill-advised remake of the Hitchcock classic The Lady Vanishes in 1979, the soundstages went dark, and Hammer, it seemed, was consigned to the cobwebs.

Then in 2007, as if following one of its own vampire scripts, the corpse of Hammer Horror films began to stir again. A Dutch producer, John DeMol, bought the rights to the back catalog and revived the production company, which announced plans to begin making Hammer-branded horror films once again. In April of 2008, the Hammer-produced web series Beyond the Rave debuted on Myspace. The follow-up releases, Wake Wood and The Resident, received little notice. But Let Me In, the 2010 remake of the hit Swedish vampire movie Let the Right One In, attracted a bit more attention. And now with the upcoming release of The Woman in Black, it appears, once again, to be Hammer time.[3]3

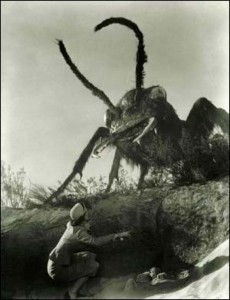

In the century and a half leading up to WWII, scientific progress represented a kind of utopian dream for a future in which the laws of nature would one by one be tamed and harnessed for the betterment of mankind. With the birth of the Bomb, that dream became a nightmare. As they always do, the horror movies of the late 40s and 50s reflected the fears of their day, and projected those nightmares onto the screen: giant radioactive ants shredded screaming teenagers, 50-foot women wrecked homes, aliens mowed down fleeing citizens with death rays. We had created a monster in the laboratory, and now we were terrified about what might happen if we were unable to control it.

When Hammer Films brought The Curse of Frankenstein to the screen in 1957, it brought these fears of scientific progress full circle: Mary Shelley’s tale of scientific hubris, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, is arguably the first science fiction novel, suggesting that the dream of scientific progress and the nightmare of unintended consequences have always existed alongside each other.

In addition to reviving the classic monsters of prewar Hollywood to embody postwar fears of scientific progress, Hammer layered in a healthy dollop of sex. In doing so they ushered in a new era of exploitation cinema as other filmmakers took Hammer Horror’s trademark style of sensuous horror and pushed it beyond boundary after boundary. Today, peering back through all those shattered boundaries, The Curse of Frankenstein appears almost quaint.

Watch it for yourself and see why The Curse of Frankenstein—and the Hammer Horror genre it launched—became such a towering influence on artists such as Martin Scorsese, Tim Burton, and Kate Bush.

NOTES:

- Much of British horror cinema can be divided into two genres: pre-Christian and Victorian. Where these differ in presentation and setting, they are unified by their common central theme: not the fear of death, but the fear of sex. In British pre-Christian horror films such as The Wicker Man and Blood on Satan’s Claw, the paganism practiced by Britons before Christianity came to the island c. 100 c.e. symbolizes original sin — the sin of a people rather than of a person. British pre-Christian horror films indulge the notion that when England was Christianized, the ancient gods were not so much driven out as they were driven underground (or simply redefined as demons) and are still worshiped by isolated clans. Human sacrifice and sexual abandon abound and are usually connected to cliché trappings of paganism: fertility, harvest, etc. Flower wreaths and gossamer gowns are de rigueur and suggest a parallel with the ongoing sexual revolution of the genre’s heyday, the 1960s and 70s. The Victorian horror films, of which Hammer films was the standard bearer, drew on fears of the same idea: that man is sinful—i.e. sexual—by nature, and it’s only the civilizing effects of Christianity that prevents us from giving ourselves over completely to our animal desires. The chief distinction between these two genres is that in pre-Christian horror, our inherent sinfulness manifests as sex, pretty straightforwardly (albeit conflated with demons and ritual murder), while in Victorian horror the sexuality is sublimated even further, with the corruption of the body through sex portrayed symbolically as the corruption of the body through violence.

- The opening credits of Horror of Dracula also set the style for all future Hammer Horror films–at least every single one that I’ve seen–with all the opening credits rendered in an unnaturally bright red.

- Sorry.

NOTE: a version of this article was first published at blog.indieflix.com