he Western is how America has chosen to tell its story, first to ourselves and then to the world. It is America’s contribution to world mythology, and like all mythology it is partly the truth, and partly a lie.

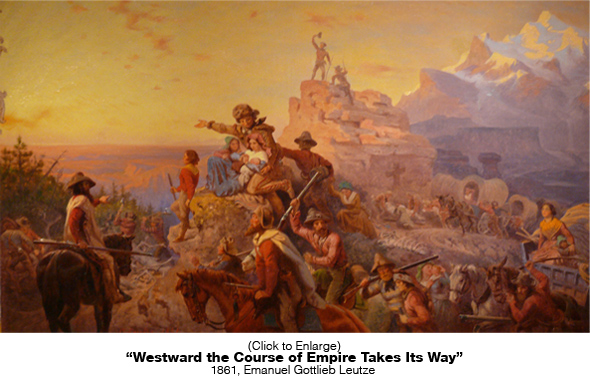

he Western is how America has chosen to tell its story, first to ourselves and then to the world. It is America’s contribution to world mythology, and like all mythology it is partly the truth, and partly a lie.  The part that is true is the story of the people, individual adventurers, who struck out from the smallness of their birth countries and crossed an ocean to a new world, a world where they would be free to live by their own code of honor, and where they could expect to reap rewards, both material and spiritual, in proportion to the strength—of back and mind—that they brought to their labors. It is the story of those labors; of the exploration of unknown territories; of the pursuit of the ever-advancing horizon and the promise it held of freedom and space. It is the story of the fight for that land, of the neverending struggle against the environment, and against the native peoples who were unwilling to accept the coming order.

The part that is true is the story of the people, individual adventurers, who struck out from the smallness of their birth countries and crossed an ocean to a new world, a world where they would be free to live by their own code of honor, and where they could expect to reap rewards, both material and spiritual, in proportion to the strength—of back and mind—that they brought to their labors. It is the story of those labors; of the exploration of unknown territories; of the pursuit of the ever-advancing horizon and the promise it held of freedom and space. It is the story of the fight for that land, of the neverending struggle against the environment, and against the native peoples who were unwilling to accept the coming order.

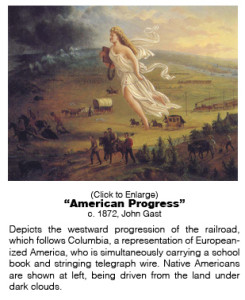

And thus we arrive at the part of the mythology that is a lie: the part that declares that the European settlers, by virtue of their race and their religion, were anointed by their god—and their weapons—as the rightful overseers of this new world. A model that had been in place for ages and would hold sway for at least a couple centuries more, the imperial model declared that no land was considered occupied unless it was held by white Europeans. Any land occupied by native brown people was there for the taking by whichever Christian nation planted the first European flag in the conquered soil.<ref>This view of the world was so unquestioned that it was seen not as a privilege, or as the theft of land from people who lacked the defensive capabilities to hold it, but as a responsibility: Manifest Destiny.</ref>

And thus we arrive at the part of the mythology that is a lie: the part that declares that the European settlers, by virtue of their race and their religion, were anointed by their god—and their weapons—as the rightful overseers of this new world. A model that had been in place for ages and would hold sway for at least a couple centuries more, the imperial model declared that no land was considered occupied unless it was held by white Europeans. Any land occupied by native brown people was there for the taking by whichever Christian nation planted the first European flag in the conquered soil.<ref>This view of the world was so unquestioned that it was seen not as a privilege, or as the theft of land from people who lacked the defensive capabilities to hold it, but as a responsibility: Manifest Destiny.</ref>

The Western Myth, then, has at its core two essentially irreconcilable contradictions. One is the freedom achieved by forcibly depriving other people of their freedom. In the main, by depriving them of life: the genocide that underlies the story of Western Expansion.

The second irreconcilable contradiction happened at a more individual level. The impulse that led many of the settlers who continued West across the continent, who were not content to put down roots along the Eastern Seaboard where they first landed, was an impulse for “elbow room.” They rejected the growing congestion and urbanism of the East and longed for the vast open spaces promised by stories of the Western frontier. But by following this impulse, by chasing those dreams of land lots of land under starry skies above, they inevitably paved the way for others. The very civilization they sought to escape followed close upon their heels, driving them—and ultimately the trails that would be trekked by the next wave of settlers—further and further west.

The greatest Westerns movies are the ones that attempt to address, or at least acknowledge, these contradictions which define the American myth. The Westerns of John Ford, Anthony Mann, Budd Boetticher, Howard Hawks, and Delmer Daves didn’t shy away from these complex issues, and so they stand today as the lasting masterpieces of the Western genre.

(The Western is even more ingrained into the American psyche than most of us give it credit for. I have a friend who has a doctoral degree in women’s literature. Her specialty is the diaries of frontier women. She hates Westerns. I can’t get her to watch Rio Bravo, a chick flick in Western drag, for love or money. But the diaries she studies are Westerns. My Antonia is a Western. Little House on the Prairie is a Western. )

(The Western is even more ingrained into the American psyche than most of us give it credit for. I have a friend who has a doctoral degree in women’s literature. Her specialty is the diaries of frontier women. She hates Westerns. I can’t get her to watch Rio Bravo, a chick flick in Western drag, for love or money. But the diaries she studies are Westerns. My Antonia is a Western. Little House on the Prairie is a Western. )

![]()

The Western has long been fertile ground for metaphor: the image of the man alone, or with a family that depends on him, surrounded by danger, in the form of small-minded townspeople, Native Americans or, frequently, the environment itself, which in the Western—as in some science fiction—often takes on the role of antagonist.

Inevitably, however, as the genre became more established and more commercially viable, movies came along that had little or no interest in using the Western as a means to address such issues, metaphorically or otherwise, and so there are at least as many escapist Westerns as “serious” Westerns, if not more. The prevalence of these escapist Westerns, where the focus was on adventure and action, and where racism was reinforced rather than examined by reducing Native Americans to cliché devices of conflict, eventually led to a drop in popularity and the Western fell out of fashion.

Inevitably, however, as the genre became more established and more commercially viable, movies came along that had little or no interest in using the Western as a means to address such issues, metaphorically or otherwise, and so there are at least as many escapist Westerns as “serious” Westerns, if not more. The prevalence of these escapist Westerns, where the focus was on adventure and action, and where racism was reinforced rather than examined by reducing Native Americans to cliché devices of conflict, eventually led to a drop in popularity and the Western fell out of fashion.

But a curious thing happened around about the time of World War II: the Western became popular again. This newfound popularity is often attributed to the success of John Ford’s Stagecoach, in 1939, but I think there was more to it than that. Even if it”s only noted later with the benefit of hindsight, popular trends in moviemaking are often found to reflect, directly or indirectly, the issues of their times. The explosion of violence in movies of the late 60s (The Wild Bunch, Bonnie and Clyde, etc.) is often attributed to attitudes about the ongoing war in Viet Nam, fed by unprecedented battlefield images piped into livingrooms by the television. The nihilism of 70s independent cinema is sometimes seen as a reaction to Watergate. In much the same way, it’s my belief that the Western became once again popular—i.e., relevant—around the time of World War II as a parallel online casino to America’s participation in the global conflict. We saw ourselves as the white-hatted gunslinger, riding into town to restore order. Westerns continued to gain popularity as the war ended, when the Marshall Plan (even the name evokes a frontier lawman) entailed American forces subduing the “savages” of Nazi Germany, and while American forces occupied Japan. Such cowboy diplomacy was very much in most Americans’ minds, and seems to me an obvious parallel to the Western myth. At the same time, growing levels of violence and cynicism began to darken these postwar Westerns, giving rise to what has been called the anti-Western, in which many of the romantic myths of Western Expansion were shattered. (See Delmer Daves’ 1958 Cowboy for an especially brutal example of the revisionist anti-Western. John Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn, 1964, and Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar, 1954, offer similarly dark takes on the corrupt heart of the Western Myth.)

With recent entries into the genre like Brokeback Mountain, The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada, and True Grit, the Western is once again experiencing a resurgence of popularity (while we are again at war, I might point out), and thus proves itself to be one of the most resilient genres in American films.

These classice westerns are all available for streaming from archive.org, an online database of copyright-free material.

The Great Train Robbery | Edwin S. Porter | 1903

One of the very first narrative films, and one of the first films of any kind to use cinematic techniques to tell a story. The earliest motion pictures tended to be a stationary camera pointed at a stage, where a story was acted out in chronological scenes. In The Great Train Robbery, the editing became part of the story, as it cut between action taking place at different locations. The Great Train Robbery is also believed to include the first “pan,” in which the camera moves to follow the action. Made by the Edison Company, The Great Train Robbery was the first film to cross the line from novelty item to commercially viable entertainment. Its success paved the way for movies as an industry.

The Santa Fe Trail | Michael Curtiz | 1940

From Michael Curtiz, director of Casablanca, a rollicking star-studded escapist Western. Includes such Hollywood luminaries as Errol Flynn, Olivia deHavilland, Raymond Massey as a crazy-eyed John Brown, and Ronald Reagan as George Custer. From the New York Times review of December 21, 1940, by Bosley Crowther: “ it has about everything that a high-priced horse-opera should have—hard riding, hard shooting, hard fighting, a bit of hard drinking and Errol Flynn.”

Death Rides a Horse | Giulio Petroni | 1967

An overlooked Spaghetti Western by Giulio Petroni. Has the distinction of starring one of the greatest faces in all of Westerns, Lee Van Cleef, who was usually relegated to the thankless role of Clint Eastwood’s sneering, leering nemesis. A frontier revenge story, filmed like a gothic horror film, with one of Ennio Morricone’s greatest soundtrack scores.

![]()

![]()

(Thanks to Vern, of outlawvern.com: I stole the title of this blog post from his awesome book Yippee Ki-Yay Moviegoer! Writings on Bruce Willis, Badass Cinema and Other Important Topics.)