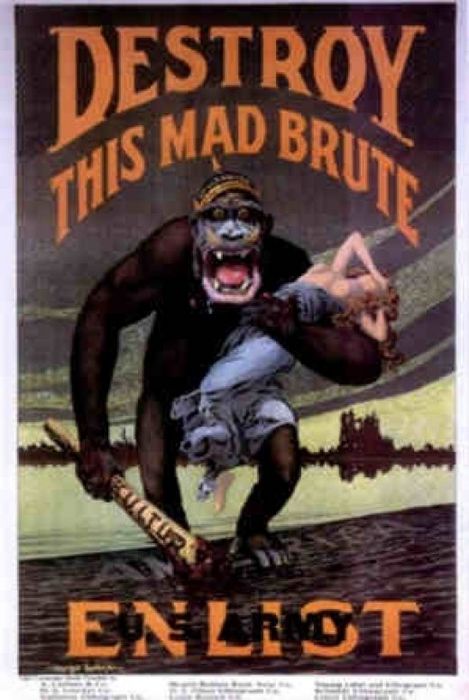

hat which we fear we call evil. In so doing we deny responsibility for our fears because capital-E Evil is an external agent: we are its victim, we tell ourselves, not its source. So, in war, we dehumanize our opponents in order to justify killing them; we blame the poor for their poverty to justify not helping them.

hat which we fear we call evil. In so doing we deny responsibility for our fears because capital-E Evil is an external agent: we are its victim, we tell ourselves, not its source. So, in war, we dehumanize our opponents in order to justify killing them; we blame the poor for their poverty to justify not helping them.

For millennia much of Western Civilization has equated female sexuality with sin and death. This is inevitable: take a patriarchal society—where men make the rules and lay the blame—add the idea that sex is sinful, and you get one of the oldest and most universal archetypes in human cultural history: the femme fatale (French for “deadly woman”).

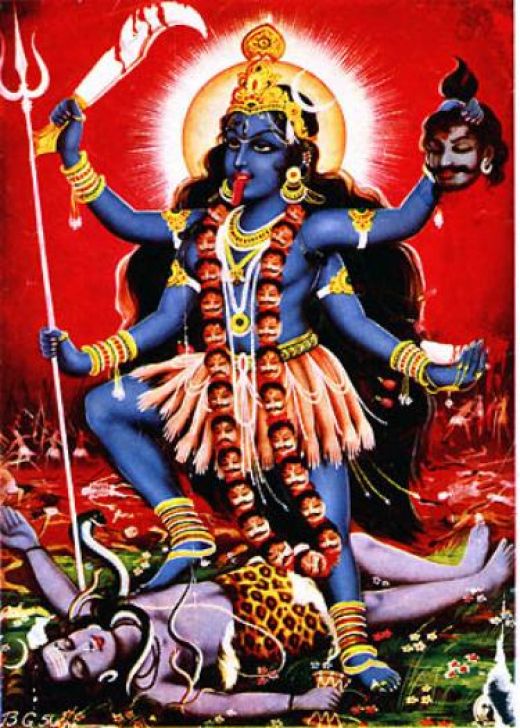

All cultures—or as near as makes no difference—have mythologized the inherently evil woman. From the ancient idea of the vagina dentata; to Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction; to Eve; to Morgan le Fey; through to modern characterizations as varied as Mata Hari, Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, and Jessica Rabbit.

All cultures—or as near as makes no difference—have mythologized the inherently evil woman. From the ancient idea of the vagina dentata; to Kali, the Hindu goddess of destruction; to Eve; to Morgan le Fey; through to modern characterizations as varied as Mata Hari, Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, and Jessica Rabbit.

During the twentieth century the glory days of the femme fatale coincided with the era of film noir, another French term that means, literally, “black film.” This refers to the shadows and dark corners of the genre’s characteristic cinematography, as well as the pessimistic and misanthropic themes that run through many a film noir. The femme fatale, a man-eating succubus conjured by male fears of female sexuality, is for many the very image of film noir: the chiaroscuro-veiled siren, a beckoning curl of smoke at her flushed lips—all femmes fatales smoke—calling you closer, closer, to destroy yourself on her rocky shore.

The streaming revolution has made many classic femme fatale films available FOR FREE online.

Detour| 1945 | Edgar Ulmer

Ann Savage scares me. Her snarling, clawing virago (Vera) is like a punishment summoned by the God of Job to teach Tom Neal (Al), our protagonist and classic noir narrator, a lesson about moral relativism. You make one lousy mistake—hide one lousy corpse from the cops and drive off in his car—and there she is, like an avenging apparition materialized from a roadside dustdevil: Retribution in heels. Detour reads like a portrait of depression, and Vera is all those inner voices of doubt, fear, and self-loathing brought to life, riding shotgun in a stolen car on a hellish road trip—Vera, virago, Virgil: if she’s a virgin it’s only because all of her defenses are lethal—to a fate beyond your worst nightmares.

Detour looks like it was made for about a buck fifty: in a few scenes, shadows and fog are unapologetically used as substitutes for physical locations; some shots are flipped, putting the driver on the wrong side of the car. But director Edgar Ulmer’s weird genius was somehow to draw an above-and-beyond performance out of his sets and locations just as he did his actors. From the inexplicably eerie The Black Cat, to Detour, to The Strange Woman (see below), Ulmer’s films are masterclasses in economy and atmosphere.

![]()

The Strange Woman | 1946 | Edgar Ulmer

An odd hybrid: The Strange Woman is both 18th Century period drama and hardboiled film noir, complete with a coldhearted femme fatale. Hedy Lamarr, who was known matter-of-factly as the Most Beautiful Woman in the World, had entered the public consciousness with a full-frontal splash of skinnydipping notoriety with the 1933 Czech film Ekstase (Ecstasy), in which she performs the titular emotion so orgiastically that rumors she wasn’t acting dogged her all her days. In The Strange Woman, Lamarr found her greatest role. Her Scarlett O’Hara. In fact Jenny Hager is an awful lot like Scarlett: she’s spoiled, manipulative, and ambitious—in some scenes there’s even an uncanny physical resemblance. But where Scarlett’s weaknesses were mostly self-destructive, Jenny’s road to wealth and power is littered with corpses: the lives she destroyed along her way.

An odd hybrid: The Strange Woman is both 18th Century period drama and hardboiled film noir, complete with a coldhearted femme fatale. Hedy Lamarr, who was known matter-of-factly as the Most Beautiful Woman in the World, had entered the public consciousness with a full-frontal splash of skinnydipping notoriety with the 1933 Czech film Ekstase (Ecstasy), in which she performs the titular emotion so orgiastically that rumors she wasn’t acting dogged her all her days. In The Strange Woman, Lamarr found her greatest role. Her Scarlett O’Hara. In fact Jenny Hager is an awful lot like Scarlett: she’s spoiled, manipulative, and ambitious—in some scenes there’s even an uncanny physical resemblance. But where Scarlett’s weaknesses were mostly self-destructive, Jenny’s road to wealth and power is littered with corpses: the lives she destroyed along her way.

Stylistically, The Strange Woman differs from most of director Edgar Ulmer’s work. His reputation for churning out economically spare B movies belied his past experience as set designer on such visually baroque masterpieces as Metropolis and M. Add to that the uncredited participation of stylist of stylists Douglas Sirk, who covered for his friend when Ulmer became ill during shooting, and you get The Strange Woman’s weird but bewitching recipe of noir shadows and Hollywood period gingerbread. The Strange Woman is a beautiful and nasty little film.

![]()

Scarlet Street | 1946 | Fritz Lang

Where to begin with Scarlet Street? It’s a masterpiece of the American cinema that can be approached from almost any angle—dramatic, cinematic, literary, historical, psychological—with nearly endless rewards. Directed by Fritz Lang, who’s surely on the shortest possible list of greatest directors in the history of film, Scarlet Street is a remake of Jean Renoir’s (another name for that short list) La Chienne (1931), which some would translate as “The Bitch.” Lang reassembled the cast of his previous film, the great but still lesser The Woman in the Window, for this descent into self-destruction and despair.

Edward G. Robinson plays Chris Cross (!), a meek little man who wears his wife’s frilly aprons as he waits on her hand and foot in return for nothing but verbal abuse and humiliation. Joan Bennett, who is perhaps best known today as mother to Elizabeth Taylor in Father of the Bride, is Kitty (!), a prostitute Chris rescues late one night as she is being perfunctorily beaten on a rainy streetcorner by her pimp, the congenitally creepy Dan Duryea. Where there is in fact nothing but cold stone, Chris sees a heart of gold—fool’s gold, as it must inevitably turn out.

Edward G. Robinson plays Chris Cross (!), a meek little man who wears his wife’s frilly aprons as he waits on her hand and foot in return for nothing but verbal abuse and humiliation. Joan Bennett, who is perhaps best known today as mother to Elizabeth Taylor in Father of the Bride, is Kitty (!), a prostitute Chris rescues late one night as she is being perfunctorily beaten on a rainy streetcorner by her pimp, the congenitally creepy Dan Duryea. Where there is in fact nothing but cold stone, Chris sees a heart of gold—fool’s gold, as it must inevitably turn out.

Scarlet Street is rife with Freudian imagery and layer upon layer of complex themes and symbols, and was probably the first film to squeak an unredeemed murderer past the ever-vigilant Hollywood censors. Rewards multiple viewings.

![]()

Please Murder Me | 1956 | Peter Godfrey

In addition to having just about the best title ever, Please Murder Me stars a 31-year-old Angela Lansbury as a scheming femme fatale who drives Raymond Burr to sacrifice himself to her murderous clutches in a desperate attempt to bring her to justice.

![]()

Too Late for Tears | 1949 | Byron Haskin

While giving a character an unexpected opportunity to choose good over evil is a tried and true trope of film noir, few movies get it out of the way as quickly as Too Late for Tears: in the opening scene, a satchel of cash is tossed from a passing car into the back seat of a young couple’s convertible. The ferocious relish with which wife Jane (the underappreciated beauty Lizabeth Scott) seizes the role of femme fatale shocks even Danny (repeating myself here: uber-creep Dan Duryea), the gangster who shows up, right on schedule, to retrieve his loot. An little-known gem of hardcore femme fatale noir.

![Best Show on Netflix? "Top of the Lake" [Streamers]](https://drunksunshine.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/1362729750825.jpg)