Welcome, drunksunshiners, to a new series: Stuff You Should Know About. Under this rubric you’ll find an eclectic, if not bizarre, array of stuff we love, and that we insist our friends love too. Think of all those things that you sometimes imagine you alone have discovered, which you find yourself obnoxiously overselling to all your friends. “You’ve GOT to read this book/try this recipe/hear this music/visit this nudist resort/etc.!” Our goal will be to highlight experiences that seem to have been overlooked, or not yet discovered, by the trendsters at large. Please let us know if you have any such favorite things you’d like to overexpose, we’re always looking for guest recommenders.

Welcome, drunksunshiners, to a new series: Stuff You Should Know About. Under this rubric you’ll find an eclectic, if not bizarre, array of stuff we love, and that we insist our friends love too. Think of all those things that you sometimes imagine you alone have discovered, which you find yourself obnoxiously overselling to all your friends. “You’ve GOT to read this book/try this recipe/hear this music/visit this nudist resort/etc.!” Our goal will be to highlight experiences that seem to have been overlooked, or not yet discovered, by the trendsters at large. Please let us know if you have any such favorite things you’d like to overexpose, we’re always looking for guest recommenders.

mmm. Pancakes. A cheaper breakfast than anything but oatmeal—not much more than flour, eggs, milk. A blank canvas for endless flavor experiments. The most efficient delivery system for butter and maple syrup short of drinking them. (Hmmm, drinking them . . . )

As good as conventional pancakes are, using the acid+base reaction of baking powder to create the little bubbles that distinguish pancakes from tortillas, there’s another leavener that reveals baking powder to be, by comparison, a dead thing.

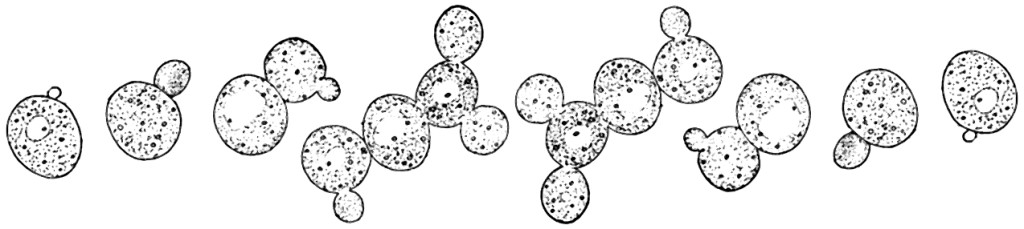

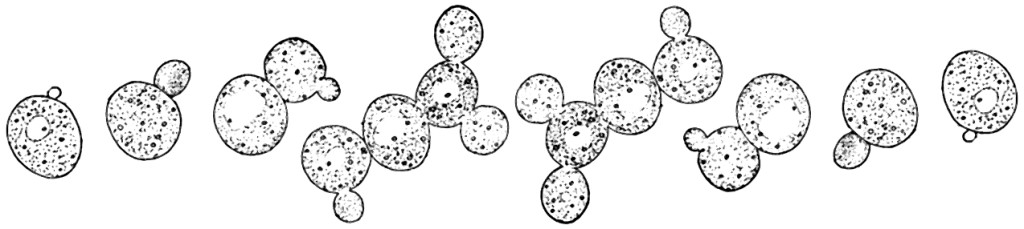

Yeast is magic. It turns grape juice into wine, it turns the dried seeds of grasses into fresh baked bread. It turns ginger into ginger ale. It lives on the bottom of the ocean, in the gut of honeybees, and raises the temperature of the Stinky Hellebore in order to attract pollinators.

Yeast is alive: it breathes in oxygen and exhales carbon dioxide. It consumes sugars and produces alcohol. These are the properties that led to yeast being perhaps the first domesticated organism, with evidence of cultivation going back at least 4000 years. Forget the wheel, or dental floss, I’d like to have been the first person who went right ahead and baked the wheat paste that had become foamy after being left out for too long and the breath of life had entered it from the very air. That ancient baker is quite possibly one of the only true alchemists in human history: transforming flour and water into a living thing, like a god creating man from mud.

Yeast is alive: it breathes in oxygen and exhales carbon dioxide. It consumes sugars and produces alcohol. These are the properties that led to yeast being perhaps the first domesticated organism, with evidence of cultivation going back at least 4000 years. Forget the wheel, or dental floss, I’d like to have been the first person who went right ahead and baked the wheat paste that had become foamy after being left out for too long and the breath of life had entered it from the very air. That ancient baker is quite possibly one of the only true alchemists in human history: transforming flour and water into a living thing, like a god creating man from mud.

And so, yeast pancakes. The exhalations of yeast give you a fluffier pancake, and its suspiria fill the house with the sensual spirits of baking bread.

The first thing I do is turn the oven on for one minute, get it feeling like a Texas summer afternoon. I like to think of it as roughly body temperature: human warmth at 98.6 degrees. (This also inflates the artificial sense of significance I like to impart to such activities.) Into a medium-large bowl goes about a cup and a half of all-purpose flour. There are those who swear by cake flour for pancakes, to which I say give me a break, but I’ll probably try it someday anyway. Sprinkle in a scant teaspoon of dried yeast, another scant teaspoon of salt, and for a hearthy depth I sometimes add about a half teaspoon of pumpkin pie spice. Not enough to taste like November; just enough to synergize with the maple syrup for a little extra personality.

I’m not a big fan of blindly following traditional kitchen mandates—just watch me bring the kettle to the pot!—so I usually ignore a recipe’s insistence on blending dry ingredients before mixing them with wet. But in this case I make an exception: wet cinnamon forms slimy clumps, very difficult to break up, so I whisk the dry ingredients pretty thoroughly to separate each cinnamon speck from its brethren as much as possible.

For the liquids, I mix them all in a two-cup measuring cup, going for a blended total volume, so I don’t usually measure each fluid separately. But in preparation for this post I tried to quantify somewhat. (Thanks here to Alexandra Bush, my amanuensis.)

Into the two-cup cup goes a rounded to heaping teaspoon of sugar, white or brown, and a couple eggs. I fork-beat the sugar with the eggs on the untested theory that the grit of the sugar will abrade the egg whites to form a smoother amalgam. Once this looks about right, I beat in three or four tablespoons of oil. Your choice here; oils like almond or walnut make the whole process feel fancier, but mostly because they’re too expensive for real people. My default is canola. Blend the oil into the egg mixture as thoroughly as you feel like, then slowly beat in your dairy liquid of choice—milk, buttermilk, half and half, cream—each produces a slightly different texture of pancake. Soy milk renders the batter a little less cohesive, with a curdled look, but results in a taller—if slightly rubberier—pancake. My default is whole milk, with cream sometimes for smaller, denser pancakes that offer a more luxurious mouth feel. Also at this stage I usually add a dribble of vanilla extract. (Dribble is the plural of drop; it’s about half a blup.)

About a cup and a quarter of milk will bring your liquids to two cups. Make sure they’re well blended, then microwave for about 75 seconds. It should be baby-bottle warm, not hot. Dump the liquid ingredients into the dry, and give it a few quick flicks of the whisk. The chief crime committed by pancake makers is overbeating the batter. This stirs the gluten awake to seize up and toughen the pancakes. Rubbery. Stir a few seconds; lumps smaller than a pea (a small pea) will melt away as the pancake cooks.

Now we come to the part of the recipe where you get to take a nap, or mow a lawn, or read a Flannery O’Connor short story. As with any yeasty project, we must take some time to let the batter rise. Here’s where the cozy oven comes into play. Put the batter in the 98-degree oven, covered—Martha Stewart would use a seafoam green linen tea towel; I use a dinner plate—and set a timer for 30 minutes.

I’ve been making these pancakes practically every morning for a little shy of six months. Working with yeast often feels more like an art than a science; my yeast recipes improve as my feeling for the process overtakes my adherence to the formula. The more you work with yeast, the more you’ll develop a feeling for it—you’re working with a living, breathing thing—and the more artful your results will become. Putting away the recipe and trusting the Force also ensures that each time you make or bake something, it will have its own personality. A guest at your table. I never measure my ingredients exactly with a yeast recipe—except sometimes with a new recipe; you have to get a feel for the clay before you can mold it into a new shape—and so each creation becomes another step on a journey, rather than a series of overfamiliar destinations. My bread is sometimes tough, sometimes soft, sometimes salty sometimes sweet. I like to think each incarnation reflects my personality at the time. But that’s probably bullshit .

Second in importance only to how hard you beat your batter is the temperature of the griddle. This is, frankly, almost impossible to get right; most of us have become accustomed to producing a few rejects while we adjust the cooking temp and time. Each stove, each griddle, is different, and you must undertake your own journey. For me, living with the tragedy of an electric stove, I preheat the griddle on medium for the last eight minutes of the yeast’s ascension. Then I anoint it with a little ghee—wait, let’s spend a moment with ghee, shall we?

You know when you melt butter, and there’s the clear yellow part, and then the cloudy white dregs that precipitate into a lower stratum? The part that burns to a bitter brown if you’re on the phone? Ghee is clarified butter; it’s the clear yellow part without the unnecessary white detritus. With an exotic Indian name. It’s what I use when I want to sautée or brown something in butter, but don’t want the little brown bits that can alter the flavor. Of course use what you want, but with pancakes it’s ghee for me. Unless I have bacon fat, which, give me a moment to myself please if you don’t mind.

You know when you melt butter, and there’s the clear yellow part, and then the cloudy white dregs that precipitate into a lower stratum? The part that burns to a bitter brown if you’re on the phone? Ghee is clarified butter; it’s the clear yellow part without the unnecessary white detritus. With an exotic Indian name. It’s what I use when I want to sautée or brown something in butter, but don’t want the little brown bits that can alter the flavor. Of course use what you want, but with pancakes it’s ghee for me. Unless I have bacon fat, which, give me a moment to myself please if you don’t mind.

Now it’s time to pour the batter onto the griddle, to kill those yeasty little beasties so that their dying breaths inspire the batter to cakehood.

When you remove the batter bowl from the warm oven and take off its cover, it will exhale that lovely velvety brewery fragrance of rising yeast. It will have increased in volume. How much is up to you; let it rise longer than 30 minutes if you like your pancakes on the airy side.

OK now this is important: disturb the batter as little as possible. A yeast bubble is a delicate thing. If you stir the batter, or bang the bowl too roughly on the counter, the bubbles will make a break for the surface and effect an escape. Smells nice, yes, but we want the bubbles in the pancakes. To this end I use a bowl with a pouring spout. Every time you swoop a ladle through your bowl of batter you are chasing bubbles out into the atmosphere. Pour gently, do not stir.

The size of the cake is up to you. Crazy people like their pancakes small. I leave a little gutter room for syrup; otherwise the circumference of my pancakes is limited only by the dish on which they will be served. Get you a big spatula.

This is the stage at which I like add the lumpier elements. Take blueberries (or other berries or nuts or banana slices or bacon bits or somebody stop me). I’ve tried all methods of incorporation. If you mix them into the batter when it’s ready to cook, you’ve disturbed and deflated it. And then you have to stir it a bit more each time you ladle another cake onto the griddle, because the blueberries sink: if you pour gently, your first seven pancakes will be berry-free, and your eighth will be nothing but. If you mix them in before you raise the batter, you end up with pretty much the same problems. The method I’ve settled on is to dot the berries (or whatever) around the surface of the batter as soon as I’ve poured it onto the griddle. Even something as slippery as a blueberry will usually be bezeled in place by the time it’s ready to flip the cake.

![]()

And when do you do that? Once you’ve had a few tries to settle on the proper temperature and time, set up a timer. For me it’s around five minutes, then flip for two more. To arrive at that time, you have to let the cake cook all the way through, then flip it just for a little bit of toastiness. You’ll know it’s cooked through when the surface appears matte instead of glossy. At this point, the bubbles that rise to the surface will stay popped when they pop; if they heal over like a hotspring mudbath you’re not quite there yet.

Flip the cake gently—only once! commit! multiple flippage leads to leathery pancakes!—and, if it’s been cooked through, just leave it long enough on the second side to tan it a little. If however you’ve been impatient and flipped early, while the top surface is still wet, let the second side cook through. Eventually you’ll find a balance of time and temp so the cake is ready to flip at precisely the moment when the “top”—which starts out as the bottom—is the perfect shade of golden brown. Please don’t be discouraged if you have to take the first few out back and shoot them. Patience pays with perfection.

Now, as to serving. If it’s a group breakfast, it can be fun to throw the pancakes at the crowd as you produce them, like fish to sea lions. If it’s a small group, I prefer to keep the oven warm and let a few cakes accumulate on a cookie sheet so we can all sit down and eat together. Serve with softened butter: these yeast cakes are soft and fluffy, and chilled butter goes at them like a chainsaw. Me, I like to butter them, then cut them across a grid of one inch squares, and THEN pour the warmed syrup: this provides more surface area and syrup channels for maximum saturation. And please, PLEASE, only use real maple syrup. I know it’s the single most expensive substance on earth, but there really is no comparison to the caramel colored corn syrup in the bottle shaped like a slave. A tip: Grade B maple syrup has more flavor than Grade A. Presumably because back when they were coming up with grades the aspiration was to produce a sugar comparable to white cane sugar, which is pale and tasteless. Grade B maple syrup is darker and maplier. But just as expensive.

When I make these for myself, I usually freeze the surplus. This works great; sometimes the reheated cakes are even better, reheating them in a conventional oven (cookie sheet, 350, 12 minutes) gives them a nice crust. To freeze them, don’t just wrap a pile in foil and stick it in the ice box. Yes, again with the cookie sheet: freeze them flat, unstacked; onesies. Make sure they’re frozen solid before you stack and store them. If you freeze them in a stack you’ll never separate them, and you’re stuck with a squat cylinder of dough that will reheat to mush. Frozen separately and then stacked, you can slide one out and reheat it whenever you need a quick breakfast.

Charley’s Yeast Pancakes

Prep time: about 45 minutes

- 1.5 c flour

- scant t dry yeast

- scant t salt

- 1/2 t pumpkin pie spice

- 2 eggs

- 2 heaping T sugar

- 3 T oil

- 1.25 c milk

- a dribble of vanilla

Or whatever; don’t be afraid to feel your way to the pancakes that seem right to you.